This sonata is affectionately known as “the other one,” since Op. 27 No. 2 is the “Moonlight.” I really enjoy this piece and spent a lot of time working on it. Before I got very comfortable with it, however, I used it for my Juilliard Artist Diploma audition, and I think I played it pretty mediocrely, resulting in not getting accepted (I thought my other stuff went well, but who knows). I was going through a mini crisis at that point trying to decide if I should continue onward with my studies, but fortunately I persevered. I then went on to study with Hung-Kuan Chen at Yale, who really helped me out with getting this piece down and comfortable. Out of my audition repertoire, this was probably the “easiest” on the surface, but I think it’s a much harder piece to play well and convincingly than many other pieces (the other pieces on my list were Prokofiev 8, Schumann Kreisleriana, some etudes, and Bach Keyboard Sonata in A minor).

We’re going to just talk about the first movement of Op. 27 No. 1. I’m really using this piece as an excuse to talk about certain pianistic concepts in context, so many of the ideas will be applicable to many if not all other pieces. I’ll try to be as stylistically agnostic as possible and present the various considerations we have as pianists, though some interpretation is bound to creep in since I’ve spent a lot of time on this piece. And, this list is not exhaustive; other pianists might focus on different things and reach different conclusions. Enjoy!

Legato

We have to talk about legato. I often ask students in masterclasses, “How do you create legato?” Invariably, the answers are always vague, with words like smooth, connected, and lyrical thrown around. Now, if you were playing a stringed instrument, the answer might be easier: as long as there aren’t any string crossings, you keep the bow moving in the same speed, and play the next notes. We aren’t considering phrasing or anything else here, just pure legato. Now, if there is a string crossing, what string players might do is have a bit of overlap, so that at a small instant in time, both strings are being played.

On the piano, we can’t actually hold notes. The loudest part of our notes are the attacks; at any subsequent point in time, the volume will be less. We always have to deal with decay, and just playing the notes one after another doesn’t result in a very convincing legato.

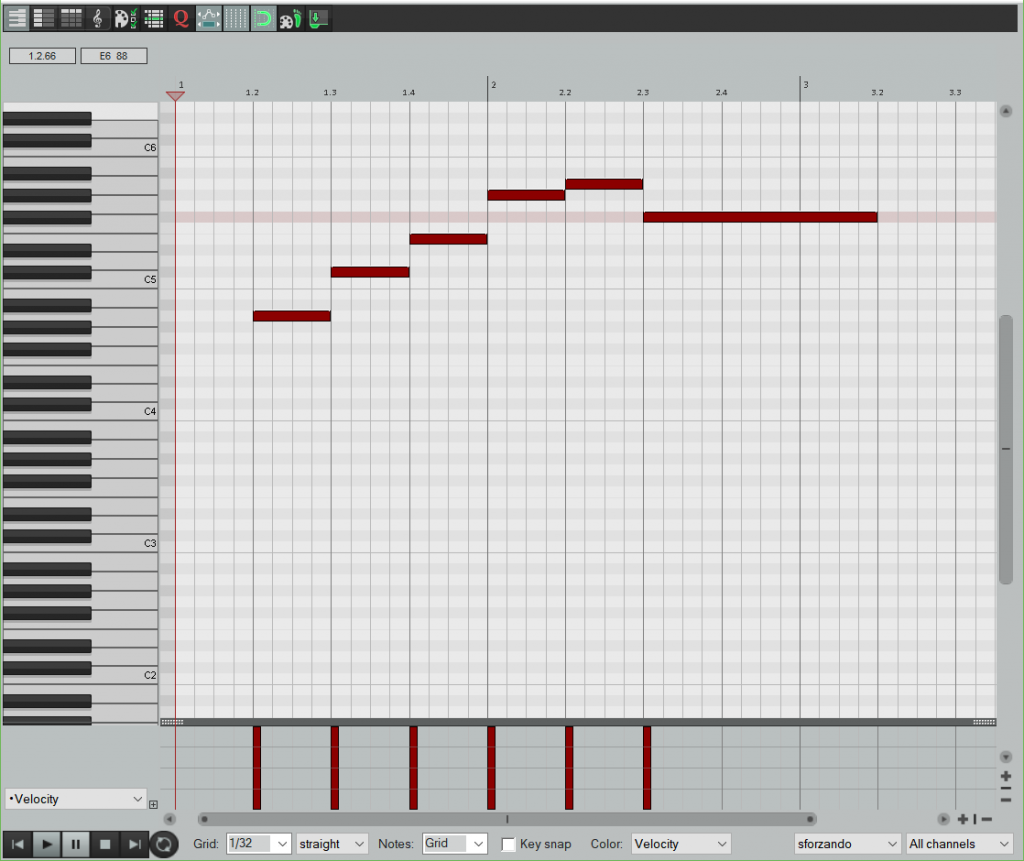

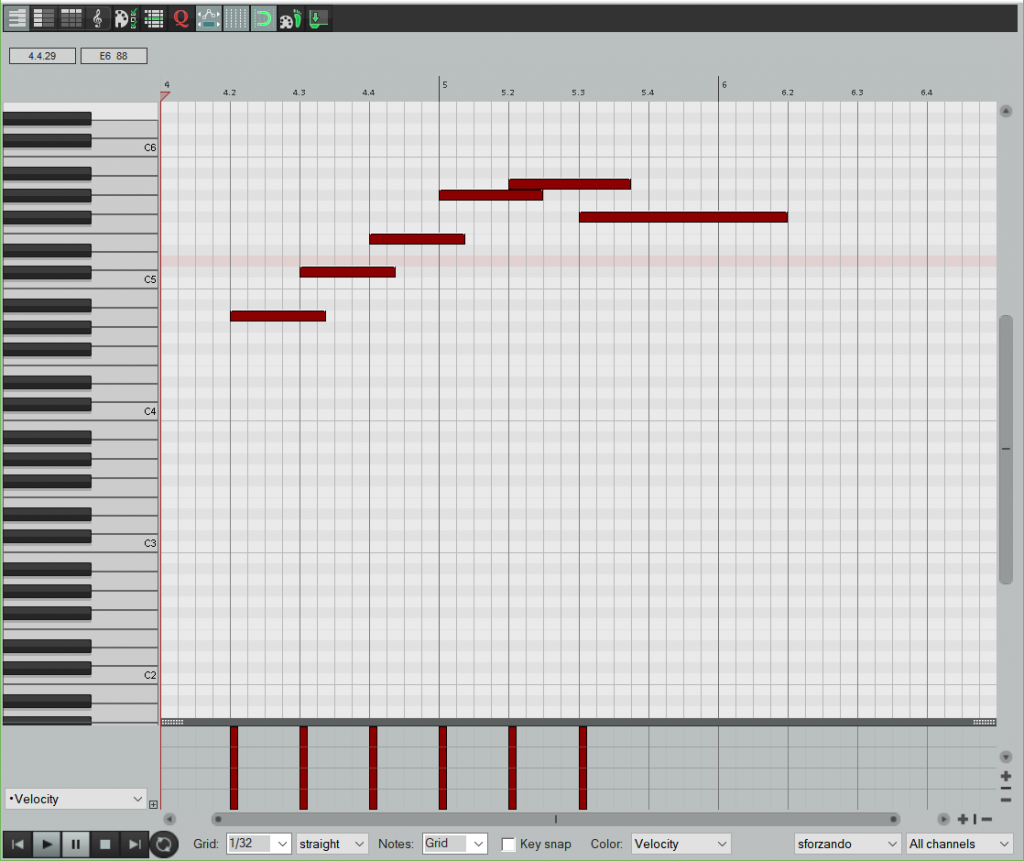

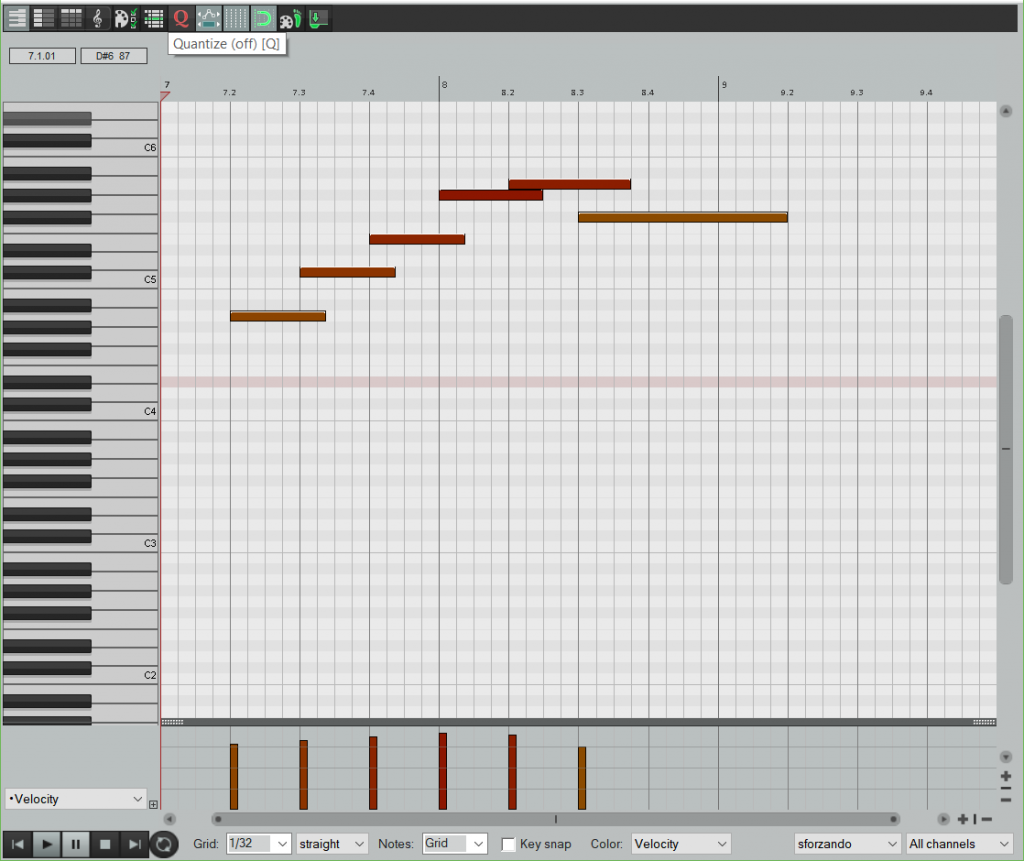

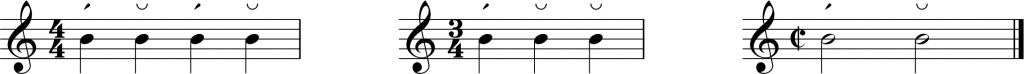

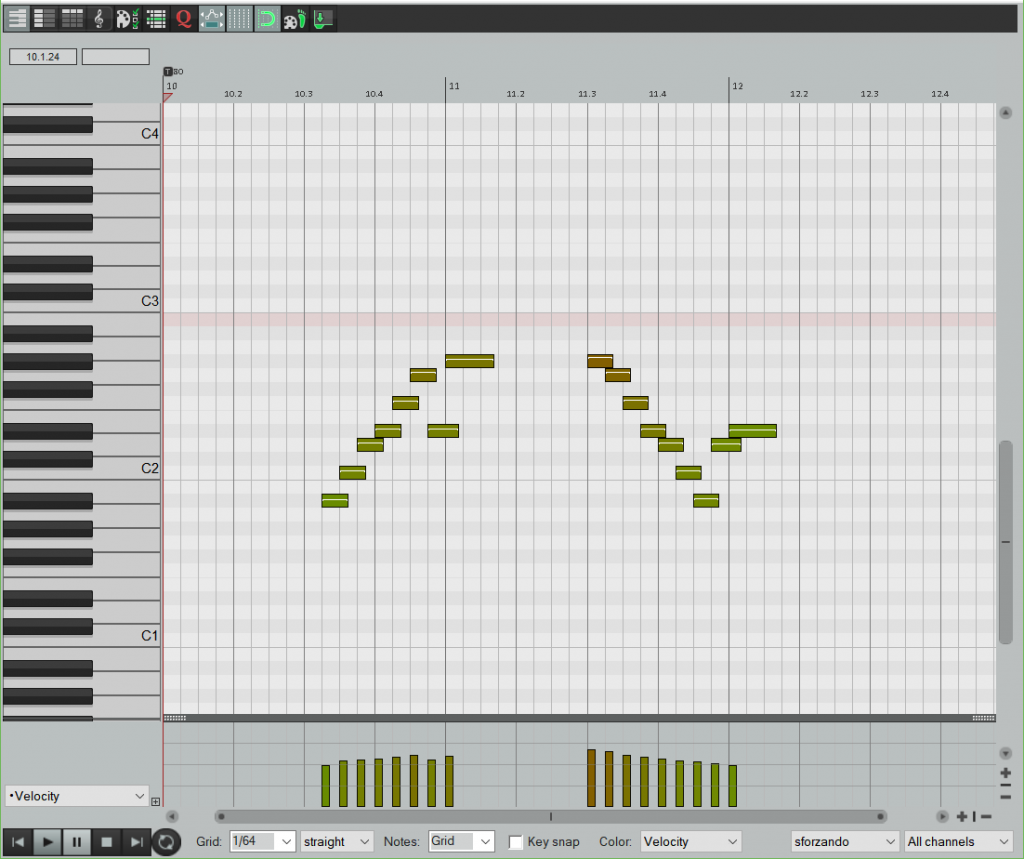

So for piano, an important key to legato is overlap of notes. This is actually a trick used in MIDI (see Fig. 1 below) when you want to create a legato sound – you actually hold the previous note slightly into the next. This creates a blend of sound, sort of like a cross-fade in audio processing. Then, as a pianist, you can use the amount of overlap, from barely any to almost all of the next note, as a tool for color and expression. You can even go the other way, and not overlap at all, in which case you get non legato or staccato or any other gradation of it.

The other component then, is the hierarchy of volumes of the notes in a legato. When just thinking of the two-note slur, we know that the second note generally has to be softer, and by quite a bit; if you play it about the same velocity as the first note, it is liable to sound like an accent. Now, in a longer legato, you can’t keep playing the next note softer, because you’ll end up at pppp after a few notes. Here’s where shaping and phrasing come into play to make sure it notes aren’t sticking out. If you are getting slightly louder throughout the legato, make sure there aren’t any unplanned decreases in velocity. If it is a general tapering, you don’t want any notes that are louder than the previous.

Fig. 1. Demonstrating Legato with MIDI

Finally, on non legato, we have to watch out that our notes are not too short. This is a judgment call, and requires adjustment in different venues and on different pianos. However, one must always be careful that the pitch is heard. I’m not a big fan of short notes where you can’t hear the pitch.

Color

We hear this term a lot, but rarely know what the person is saying when they want “more color.” In a way, it’s not a very helpful term, but we can talk about a few things that might help with “color.”

First is voicing. Simple voicing can be thought of as just bringing out the top, or the bass, or both the top and bottom voices. But, at its most complete, voicing is the relationship between all of the notes in a chord, so when we voice chords, we can’t just look at the top and the bottom. Every note in the chord needs to be balanced so that we can achieve the sound we want. Looking for a darker color? Try voicing with more bass and tenor. Looking for more body? The middle voices can help with that. Looking for more sparkle? Don’t just think about the top note, but also try to balance the second-highest note so you could some good overtones going on.

Then, you have the right pedal. Pianists tend to go on autopilot with their right foot, but I think the pedal can be one of the most expressive tools in our arsenal. My former teacher Edward Francis used to always ask, “What part of your body plays the pedal?” The answer is “Your ear!” This facetious response points to the fact that the pedal really can’t be dictated; its use must be adjusted to the piano and the hall. Every piano has a different “curve” to its pedal, if you think about a graph where the x-axis is distance depressed, and y-axis is the sustain. In fact, different sections or strings of the piano might behave differently, and we need to adjust relatively quickly to these differences.

So, color from the viewpoint of the pedal can be using less, using more, using none at the attack of the note but then adding some as the decay kicks in, or even putting the pedal down before you play a note. Then, you have full-pedal, half-pedal, a quarter, three-quarters, or any amount. We should use the full range of pedal that the piano has to offer, not just binarily.

Now on to the una-corda (or more like due-corde in modern pianos). Again, I would advocate for using the entire spectrum of the shift pedal. Depending on the piano and how old it is, the hammers might have developed hard spots where it has been hitting the string, and the parts in between will be softer. You can hear this as you gradually shift back and forth while repeating a note. Sometimes, when we want a color change, we have to find the perfect amount of shift, because oftentimes, doing a full shift results in a very unattractive sound because of the grooves on the hammer or other mechanical issues of the piano (like hammers hitting the next note).

Subito

The last technical thing is how to deal with the subito p and f. Really, a pianist just has to become comfortable with how much space is needed before or after, and adjust it to the hall and piano. It is our job to find a way, using both pedal and timing, so that the piano is effective and that it will actually be heard after the forte section.

Andante.

Oh boy, this movement… So simple, yet so difficult.

Oh boy, this movement… So simple, yet so difficult.

Structure

This sonata is interesting in its construction, because it is almost a reverse sonata: the first movement is a rondo, second movement scherzo-trio, third movement slow, and fourth movement sonata-allegro (Daniel Shapiro has pointed out that it is sonata-rondo.) (the order of the scherzo-trio slow movements is not set in stone as sometimes Beethoven has the slow movement come first, and other times not. The outer movements however are.)

So, we have a rondo, not even a sonata-rondo: A B A C A, and since each part is repeated (or written out with variations), it is more like AA BB AA CC AA. Easy enough.

Harmony and Counterpoint

Really, the simplicity is evident. Lots of tonic and dominant, with secondary keys on super-tonic, and then the parallel major of the relative minor (C Major in this Eb piece). Within each key center, there isn’t much craziness either.

I think the counterpoint makes this piece quite difficult, as the left hand is less accompaniment-y compared to other examples; it has its own character, and even gets the melody switched onto it in some of the variations. Furthermore, there is some four-voice action in many of the phrases. I can almost imagine this being played by a string quartet.

So what’s so hard?

First, tempo. We have Andante in cut-time, which means you should feel each measure in two. The difficulty then lies in finding a suitable tempo that is not too slow (since it’s not Adagio), but slow enough that it doesn’t sound hurried.

Second, phrasing. The right hand is two quarters and a half, with the quarters being portato (slurs with staccatos). Should we interpret this as down-down-up? Up-up-down? Then we have to fit it with the larger phrase. Do we emphasize the first and third or the second and fourth measures of the phrase more? How do we really do the portato on the notes? And, all of this in pianissimo!

We haven’t even talked about the left hand. That legato line is really hard to get smooth and even, especially with the crossover. Then we have a non-legato arpeggio going down at in the last measure of the phrase.

And… that’s just the first four measures.

Here are some ideas

Regarding tempo, I think the Andante can be really thought of in the quarter-note tempo, and I like around 80 bpm, a bit faster. That seems to be within the range of a typical Andante. However, one should feel the phrasing and beats in terms of the half-bar, as the time signature suggests. I think if you instead do Andante in terms of the half-note, it will be way too fast. Conversely, if you think quarter-notes as your unit of time, your playing will become too vertical.

Of course, there will be fluctuations depending on the music. For example, in the B section, there is a slight character change, and even a chance for some nice color changes. In sections with nice slurs, you can play a bit differently, maybe with more friction (or more flow!). But overall, I think the above suggestions hold well for the piece.

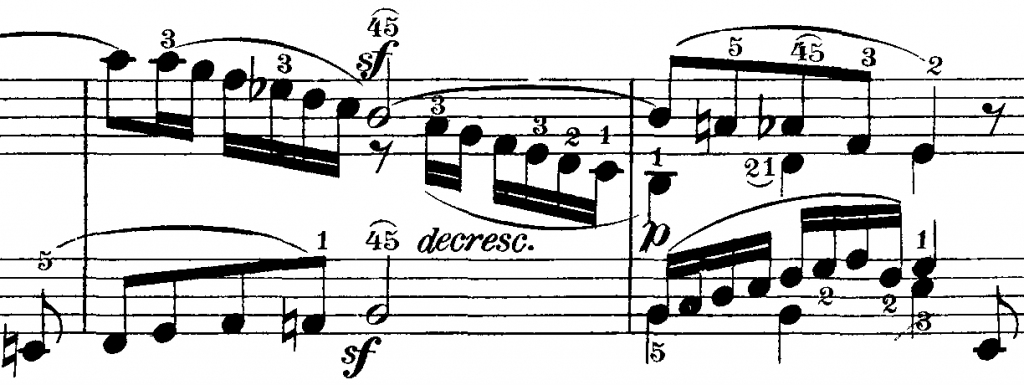

Fig. 2.

After I studied with Matti Raekallio, I was convinced that oftentimes music phrased from the start of the phrase sounds more elegant and stylistically correct, especially for pre-romantic music. That’s not to say you must always do it that way, and in fact that would be awfully formulaic and mindless. However, it’s a good guideline, because the position of beats has always been held in an important hierarchy: there are strong beats and weak beats. In 2, the first beat is strong and the second weak; in 3, the first is strong and second and third are weak UNLESS it’s a dance where the emphases might be displaced; in 4, strong-weak-strong weak, with a larger grouping of strong-weak between the first and second halves of the measure; etc. Again, this is a general guideline that is oftentimes subverted. But, it’s important to know what’s normal so that you have something against which to juxtapose the strange and abnormal.

An agogic accent is an emphasis by virtue

of being longer in duration. – wikipedia

Now, even having decided that, the right-hand phrasing is still difficult, because the half note, which is on a weak beat, is accented agogically by its length. So we have to counteract that natural accent… or do we? Maybe we do want the second beat stronger, in which case it would sound up-up-down. But, we do have to consider that the start of the measure should be strong…

Personally, I think there is a balance, and each pianist has to find for themselves how they want to phrase these measures. Even after all that deliberating and phrasing, it must be done in a subtle way as to not disturb either the dynamic or the character.

Fig. 3.

The left-hand presented a huge problem for me. After hours of practicing and working with Mr. Chen, I realized that not only was my cross-over from the thumb to the third finger bad and slow, but my thumb was prone to come in early, because of how I was playing my thumb. Basically it came down to the fact that I use more finger action and less rotation on my third and second finger, but more rotation on the thumb. The contour between the black and white keys can also prove a challenge to getting it completely even. Then, I had to make sure that the amount of overlap between the legato notes stayed the same whether there was a crossover or not.

That’s my experience, and you will most likely have different problems since our hands are so different. My suggestion is to sit down and diagnose why the legato is not even: see which fingers are coming in early or late, and see if you can spot a pattern in the unevenness. Then from there, you can try to find a physical reason for the inconsistent notes, and once you pinpoint these habits and tendencies in your technique, you can begin to address them. Don’t let yourself off easy!

The Feel

Finally, for this first movement, a big challenge is what to do in the large scale. Many of us, especially if we’ve been taught a certain way, feel that music should always be going somewhere, that there should be a starting point, a direction, and an arrival. This is certainly true of a lot of music and of many phrases. But, I think this movement as a whole defies that notion. Sure there is “movement” within each section and within phrases, but there is something very static about the larger picture. Each section is self-contained, and the character within each section is mostly unchanging. Maybe we are too obsessed with always going somewhere, especially being young and impatient and uncomfortable with being still. Perhaps this music should just be, and we should just let it exist and be content with it.

I had the hardest time with this concept. I tried to show too much and do too many big-picture ideas when what I needed to do was to focus on and internalize every detail of the music. All of the musical decisions have to happen within the character and “space” of the piece, and I had to learn to feel comfortable staying in that “space.”

I loved It! Thank you! Just hope we pianist won’t be replaced by MIDI 😉

Sean: Not entirely convinced that the 1st mvt. is a rondo. I think it is a quasi-set of variations! The “b” and “c” sections are kind-of-paraphrases, or, somewhat loosely speaking, “variations” of the ‘a” material. (And of course the A material is altered or varied very slightly and simply [intentionally so] upon each return of it).

And by the way the main thematic section of mvts 3 and 4 are also paraphrases of the opening A section of the 1st mvt(!) And isn’t the last mvt a sonata-rondo form? Anyway, best wishes Daniel

Yes I guess the last movement is a Sonata-Rondo because the first theme comes back in the beginning of the middle section (and it does return to Tonic), but it really feels like a “development” to me, rather than a contrasting section, and I always thought Sonata-Rondo had a relatively unrelated C section. Anyways, I’ve never liked the distinction between sonata and sonata-rondo =P

First movement is only variations in the A sections, and Schubert does that a lot in his last movements, the sections in between don’t feel like they’re connected to one another. Yes the B section has the same rhythm, but the harmonic rhythm and phrase structure is different. I get what you’re saying about it being kind-of-paraphrases, but it seems closer to Rondo than Variations to me.

Nice to hear from you!

Thanks for the post!

Thanks!

I LOVED your explanation of “legato” using midi — haven’t heard any other way to explain it better!